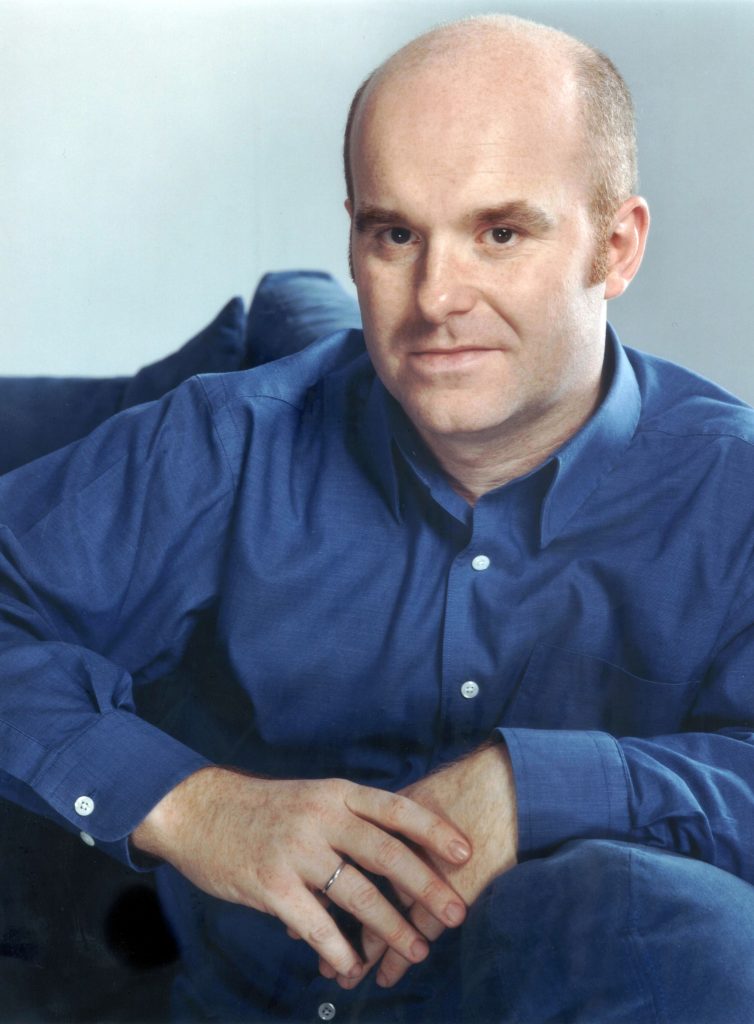

Laurence Cummings in conversation with Nikki Lloyd, NLC soprano, shortly before our Spring 2012 concert.

Its official! Laurence Cummings is to join our beloved Janis Kelly as Patron of the choir and NLC couldnt be happier. In doing this he completes a hat trick of generous gestures toward us. The first, taking time out from his unbelievably busy schedule as Professor at the Royal Academy, Handel House trustee, conductor, performer, recording artist and all round Handelian (and nice guy) to be a guest speaker at NLCs recent residential weekend and second when he made time for this interview between RA lectures whilst sitting on a park bench in the snow! Such is Laurences passion for Handel and 17th and 18th century baroque music that sub-zero temperatures werent about to dampen his enthusiasm.

Laurence doesnt ordinarily work with amateur choirs and as ever we have our Musical Director Murray Hipkin to thank for the calibre of musician that we have access to. When I tell Laurence that NLC consensus suggests he was one of our most popular guest speakers hes very generous with his comments on the choir.

Its a great group. I was very impressed by the session we had and very moved that everyone could stand up and perform in front of each other. It was a lovely atmosphere.

Specifically there to enlighten us on the historical background to tonights piece Israel in Egypt and give his informed opinion on the accurate nuances of performing it, I asked Laurence if its an oft performed piece. Its one of the more performed oratorios because its largely done more by choral societies and choirs but actually its still not done very often at all. Its such a great piece it deserves more outings and the double choir element is fantastic, making it very exciting.

Whilst speaking to Laurence I discover that we are, in fact, in the midst of a baroque revival. Id assumed that 18th century music, especially Handel, had always been as popular as it is today (after all theres nothing that secures bums on seats quite like the word Messiah on a flyer) but I was surprised to find that thirty years ago there wasnt nearly the same interest. Laurence feels one reason for the current resurgence is, more research has been done so we understand more about how it was performed and I think its music that responds well to the older instruments and a more articulate style. Previously people felt it was a bit earthbound, shall we say.

Though usually rare for amateur choirs, NLC often performs music from this period with what Laurence terms historically-informed instruments. The subsequent distinction in the sound is, an awareness of where to lighten off and where to find the light and shade but the main difference that characterises between modern playing and baroque playing is the internal phrasing. With baroque playing there are little peaks and troughs rather than one long continuous line that you get more with later 19th century music.

I ask Laurence to clarify what epitomises baroque, Yes its rhetoric really, every time a composer uses a text youre very aware of its emotional meaning. The idea that people are moved through music, you give them a painful harmony, then release them, its almost playing with the audience if you like, of manipulating their emotions, hopefully in a good way.

It was this element that ignited Laurences passion for baroque music whilst an organ scholar at Oxford. Prior to that his initial musical inspiration came from his grandmother who played piano in a cinema in the dying days of the silent pictures and then later in a dance band. He sang with the church choir (Ive always done a lot of singing) and took up piano and then organ at twelve, but it was at Oxford University where, as an organ scholar at Christchurch I had a slight crisis of musical conscience because although I liked the music I was performing I didnt feel passionately about it whereas I did with baroque and 17th and 18th century music.

I ask Laurence to describe its attraction for him. I think its the very immediate rhetoric, that youre forced with every gesture to find a meaning for it. I loved the sound of the harpsichord and what that could do and I really loved the fact that most baroque music making is social music making. Theres something particularly democratic about baroque, whether your conducting or playing its a culmination of things rather than a dictatorship.

After Oxford Laurence went onto the Royal College studying with Robert Woolley and Catherine Mackintosh, a period that he describes as, a great time of my life when I suddenly felt that everything was falling into place and I knew what I wanted to do, which at that time was play the harpsichord. Since then of course Ive branched out into conducting.

Fifteen years ago Laurence became Head of Historical Performance at the Royal Academy of Music, which he describes as an amazing learning experience and five years later he took over the running of the annual London Handel Festival. This year theyre performing Riccardo Primo and the Dublin version of Messiah. Again I had to confess my ignorance at not knowing that Messiah has different versions but Laurence assured me people think there is a version — the orange Watkins Shaw book that we all know and love — but actually there are lots of variants. Handel changed it because he had different singers, for artistic reasons, so you could argue that hes improving it but thats subjective, you cant prove that. The truth is he was a practical man so he was changing things all the time and of course if he were here today hed probably change things yet more.

Laurence is also a trustee of the Handel House Museum organising concerts, schools programmes, composition projects all with the purpose of ensuring that the visitors experience is enhanced by live music. Ive barely touched on Laurences hectic performing, conducting and recording schedule but suffice to say this year he goes to Gottingham Festival in Germany, then to Gartingdon conducting Vivaldis lOlimpiade followed by Glyndebourne for Purcells The Fairy Queen, and finally a Handel pastiche in Zurich and Messiah in Lyon. In 2015 Laurence will be at New Yorks Met but hes sworn to secrecy on this one (but it is by Handel!).

I ask Laurence if theres much more to explore in his expert niche and the excitement in his voice is palpable when he says that the instruments continue to teach so much and besides theres still so much he hasnt played yet. I read in another interview where he was asked if he ever felt like playing something a bit different and he laughs as he confirms, I … dont really. I love listening to other music but I dont feel I have a strong thing that I need to say about it. Its this total immersion and infectious sense of wonder in his era of choice that makes Laurence the thoroughly enthralling and respected authority that he is, I do other early classical things as well so Im not just stuck in baroque but I wouldnt want to venture out of the 18th century very far I think.

Murray on Laurence:

It gives me great pleasure to announce that the renowned Handel interpreter, Laurence Cummings, has agreed to become a Patron of the North London Chorus. Laurence and I first worked together in 2000 when I was assisting the conductor Harry Christophers (of The Sixteen) for the ENO production of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea and Laurence was playing the harpsichord. Since then he has returned to ENO on numerous occasions as conductor, most recently for Deborah Warner’s staging of Handel’s Messiah, Monteverdi’s Poppea and David Alden’s staging of Radamisto, for which I was his assistant. His way with Handel has been a constant source of inspiration to me and my ENO colleagues and he has taught me practically all I know about how to approach this astonishing music. I am proud to count him among my friends and although I have always gone to him for generous advice whenever NLC has worked on baroque music, I am truly thrilled that he has agreed to formalise his relationship with us by becoming Patron.